A cartoon depicting Willingdon and Gandhi

At the end of his term in 1936, Lord Willingdon, the departing Viceroy of India, could look back in satisfaction. Five years ago, when he had arrived, the country was in disarray. In the throes of the Great Depression, discontent amongst the public was widespread. Congress’s Civil Disobedience campaign was proving to be successful, having paralyzed the British administration. Worse, Willingdon’s predecessor, Lord Irwin, had tried to buy off the movement by negotiating one-on-one with Mahatma Gandhi, leading to the famous Gandhi-Irwin Pact. In Willingdon’s book, this was a grave mistake, which elevated Congress to a level equivalent to the British government.

During his tenure, Willingdon tried to put things back on track. He crushed the Civil Disobedience campaign, rounding up thousands of Congressmen and outlawing most of Congress organizations. By 1933, the campaign had to be suspended due to lack of enthusiasm. Willingdon never granted Gandhi a one-on-one audience and insisted that Congress was just one of many political voices in India. Over Congress’ vehement protests, he introduced a new constitution to govern India in 1935. All in all, by the time of his departure, things were looking up. Congress seemed to be in disarray and British officials felt confident that the party will soon split because of the infighting between the Gandhians and the Socialists. The upcoming elections of 1937, in which they expected Congress to perform poorly, would prove for once and for all that the party could not claim to speak for the entire country. Willingdon could have scarcely believed that only months after his departure, Congress would emerge united and stronger than ever before. And it would do this by using the instrument he had left behind – the 1937 elections.

Strangely, historians have largely ignored the 1937 elections, treating them as a trivial step in the inexorable march of the Indian Independence Movement. In fact, as we will see, the elections played a pivotal role in setting the course of Indian history. The tradition of elections had existed in British India long before 1937. However, in these elections only a few could vote and victors were usually given only nominal powers. Bureaucrats appointed by the British wielded most of the power, no matter who got elected. The new 1935 Constitution of India changed this by greatly expanding and deepening democracy in the country. In 1937, 13% of the population was eligible to vote (from the previous electorate of a mere 3%). The new constitution gave voting rights to women for the first time (ten years before France). The constitution also allowed victors to form provincial governments, which would have wide-ranging powers.

If the new constitution was more democratic, parts of it were also plain weird. Along with the general seats, it set aside certain seats which were reserved for minorities. These reservations were for religious minorities like Muslims, Sikhs and Christians; but also for other kinds of “minorities” like labor, commerce and land-holders. The seats for the Scheduled Castes were reserved under an even more convoluted formula. There were two rounds of elections – first round, in which only the lower castes could vote and elect four candidates; and second round, in which all Hindus could vote and decide the final victor.

The text reads: “You are both thirsty and I’ve brought you down to the tank, but you seem to prefer fighting to drinking. I may be forced to adopt a scheme of compulsory watering”. It encapsulated the British perspective of Hindu-Muslim Antagonism

This distribution of “Communal Award” ensured protection of the minorities, but it was also an attempt to deny any one party, like Congress, to dominate the elections. In fact, the Congress faced plenty of competition from other parties. There was, of course, Muslim League, the only other party which could claim some sort of pan-India presence. There were also other minor national parties like Hindu Mahasabha. But the real challenge to Congress came from provincial parties (just as regional parties dog Congress and the BJP today). In Madras, the anti-Brahmin Justice Party was far stronger than Congress. In Punjab and Bengal, two Muslim-majority states, Congress lagged behind Hindu-Muslim unity parties like the Unionists and Krishak Praja Party. In United Provinces, it faced off the National Agriculturists, the party of zamindars (we will look at some of these parties more closely in later posts). In addition, there were hundreds of independent candidates, with strong local bases, willing to throw their hats into the ring.

Not that Congress needed any help in sinking its fortunes. Its own members were doing a pretty good job of it by persistently fighting with each other. To begin with, the party couldn’t decide whether it even wanted to contest the elections. Jawaharlal Nehru, party president at the time, and the Congress socialists were vehemently opposed to the idea of contesting the elections. They wanted Congress to launch another civil disobedience campaign and take the fight to the British. Congress Right Wing, led by the trio of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Rajendra Prasad and C Rajagopalachari, were more ambivalent towards the idea. At the time they were engaged in a power struggle with the socialists and, thus, by default they found themselves in support of the idea of elections. The real enthusiasts for elections were the provincial leaders of the party, who had the opportunity to gain real power for the first time.

This painful debate over elections dragged on for almost two years. Finally, Gandhi ended the deadlock by brokering an absurd compromise: Congress will contest the elections but it will decide later whether to accept the office; should it win. In effect, it decided to keep the country in suspense about what it will do if it won the elections. The fact of the matter was that if the party chose to stay on the sidelines, some other party or coalition could have ended up winning the elections, gaining power and becoming a national challenger to Congress. It was to pre-empt such a possibility that Congress plunged into the electoral politics.

In the Congress Session in Faizpur 1936, Nehru was elected as party president for the second time in row

This was the first time when Congress as a whole contested elections. The challenge was to transform this decades-old protest movement into an election machine within a few months. Once the compromise had been reached, the entire Congress leadership dove into accomplishing this goal. The division of labor was clear-cut. Right Wingers, under the party boss Sardar Patel, took charge of organizing the party, choosing candidates and raising funds. Nehru, with his charm and popular appeal, became the star campaigner for the party.

The greatest strength for the party was its ability to attract local-level political operators. Patel had set forth two conditions for choosing candidates: they should have a real chance of winning and they should be able to finance their own campaigns. This meant that the candidates were often people who already had a political base in their constituency, usually the local zamindar or businessman or “men of local standing, substance and influence”. Such people had been active in local politics for decades. Faced with the option of either going against the formidable Congress machine or simply joining it, many chose the latter. Countless career politicians of other parties, who had stayed away from Congress as long as it was not contesting elections, now began defecting to it. Several old Congress hands saw themselves being replaced on the ticket by local magnates who had recently joined the party. For example, out of the 70 Congress MLAs elected in the Central Provinces (modern-day Madhya Pradesh), only a couple of dozen had attended a Congress session before in their lives.

The second strength for Congress was its organizational power. The party had decades of experience in organizing protest movements. Now all that energy was put into election campaigning. In United Provinces, Nehru’s political manager Rafi Ahmed Kidwai was famous for knowing every single voter list down to each locality. On the day of the election, he commandeered all the vehicles in UP and Bihar, not only for the party’s use but also to ensure that no one else had vehicles to ferry their voters.

The third advantage, of course, was the fact that Congress was home to some of the best political minds in the country. Gandhi’s name alone was worth millions of votes. After the elections, one irritated British official claimed that a majority of voters saw the ballot box simply as “letter box for Gandhi”. Then there was Nehru, who zigzagged across the country, using a plane, to campaign for Congress. Heavily suffusing his speeches with socialist ideas, he managed to evoke passions and aspirations of the masses like few could. The irony was that Nehru had opposed the idea of contesting the elections. Even now, while he campaigned to win, he maintained that Congress must reject the office upon victory. While drafting the party manifesto, Nehru made it clear that the only reason Congress was in the elections was to reject its results and “wreck” the 1935 constitution.

It was effectively a negative promise, a promise to do nothing if Congress won. As the elections neared, this became a major problem for the party, since it could not really offer anything material to the public but only lofty principles. In fact, even weeks before the election, there was no national theme for it, no major issue at stake. The result was voter apathy. One journalist noted that despite the enlargement of the franchise people didn’t seem to “care much about what is going to happen”. This was a dangerous situation for Congress. Lacking any national issue to rally behind, individual personalities rather than the party label would be the determining factor. In places where Congress had weak candidates, party’s name would not be enough to push them across the finish line. Moreover, victorious candidates would be harder to control since they could rightly claim that they had won on their own merit.

It took the skillful maneuvering of Nehru to change these dynamics. A couple of weeks before the elections, Nehru declared that India had only two parties – Congress and the government. It was a simple but genius move. In effect Nehru was saying that every vote for Congress was for freedom and every vote for any other party was against independence and in a way unpatriotic. By framing elections this way, Nehru had lumped all the other parties together as a proxy for the British Raj. Political leaders like Muslim Leagues’ Mohammed Ali Jinnah obliged Nehru by taking the bait and responding to the charge. Within a week, Nehru’s statement was a full-blown controversy, dominating the headlines. The charge was refuted from many corners. As one newspaper noted, Congress may be the biggest party but “there are millions in India who do not owe allegiance to the Congress, nay, are stout opponents of his [Nehru’s] policy and programme”.

Herein lay the genius of Nehru. While the millions did oppose Congress, he knew that they were going to vote against Congress anyway. His statement was aimed at the rest, who now galvanized under Congress’ banner. Over the next few days, Congress leaders drummed this message into the electorate repeatedly, painting all non-Congress parties in the same shade as somehow “anti-freedom”. Many non-Congress politicians, with perfectly respectable nationalist credentials were now declared “reactionary”.

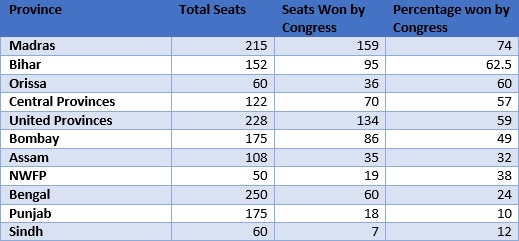

The result was a solid victory for Congress. Out of 1595 seats, Congress bagged 719. Out of eleven provinces, it won outright majority in five – Madras, Bihar, Orissa, United Provinces and Central Provinces – and near majority in Bombay. No other party came even close to its performance. Nevertheless, the extent of its victory must not be overstated. Overall, it had won only 45% of the seats, less than even an absolute majority. In today’s India, such result would have resulted in an unstable coalition government.

The problem areas for the party were the five Muslim-majority provinces – Punjab, Bengal, Assam, Sind and North West Frontier Provinces. In these places, Congress was hammered by the regional parties which were built as inter-religious coalitions. In their post-election analysis, Congress leaders admitted that the real problem was that the party had not seriously tried to win the Muslim vote. In many places, it had not even tried to contest the seats reserved for Muslims. Tellingly, the Muslim vote, which Congress did not court, did not automatically go to communal parties like the Muslim League. Instead, much of it went to Hindu-Muslim regional parties. It was evident that Indian Muslims had lost faith in Congress, even though they were not yet prepared to throw their lots with the League. This will change by the next election in 1946.

Moreover, Muslims weren’t the only ones amongst the millions who were “stout opponents” of Congress. Even in Hindu-majority provinces, where Congress had managed to secure clear victories, there were plenty of seats won by other forces. Significantly, 385 of 1595 seats were won by independents. This was really the key to understanding the situation. There was plenty of opposition to Congress in the country. In fact, a majority of voters did not vote for the party. However, there was no real anti-Congress party which could mobilize this support under one banner. The opposition remained scattered and disorganized. This situation would continue for decades after the independence, where disparate forces opposing Congress would never be able to unite as one coherent opposition party. This situation would not change until the 1990s which saw emergence of the BJP.

And so, while Congress had not swept the polls, it did emerge as the strongest victor, head and shoulders above any other party in the country. Now no one could deny its rightful claim to be the sole voice of the Indian people. The election result ended up weakening the British hand and strengthening Congress. As the fulcrum of power tilted towards the party, millions rushed to join it. In 1936, Congress had only half a million members. By 1940, this figure had climbed to three million.

The overwhelming victory of Congress also settled the debate on its acceptance of office. Nehru and other radicals continued to fight the good fight, even after the election results came out, but by now the gravitational pull of power was too strong for anyone to check. In July 1937, Congress leaders took oath of office, marking the beginning of a new era. Not only did the party form governments in the six Hindu-majority provinces, it also managed to snag Assam and North West Frontier Province, where it could build coalitions. Only Punjab, Bengal and Sind remained out of its grasp.

The party’s experience in power left a deep impact on Indian history. It served as Congress’ audition for deep-rooted power centers like the Big Business, the civil service and the zamindars. By adopting a moderate tone in the government and not undertaking any radical measures like wholesale land reforms, the abolition of bureaucracy or massive wage increases, Congress managed to convince these groups that its rule would not be all that different from the British Raj. Over the next few years, these groups increasingly moved towards Congress’ camp, making a case for independence much stronger. The governance experience was also a tremendous learning opportunity for the party, creating a legion of provincial-level leaders ready to take power once the British left. This was in stark contrast to many African and Asian countries, where colonial powers just up and left after their independence, leaving behind chaos, where no one knew how to govern.

But perhaps the most lasting legacy of the 1937 elections was the transformation of Congress into an electoral machine. In its quest to win the elections, the rank and file of the party changed from idealistic satyagrahis to shrewd political operators. All the while, the top echelons of the party was still dominated by principled leaders dedicated to the original ideals of the party. In fact, leaders like Nehru and Patel did not even contest seats for themselves, refusing to jump into the murky business of electoral politics. As one historian has noted, “The ideologues and zealots now stood at the head of an influential Congress party, the body of which consisted of men whose interests were often less idealistic and more mundane.” The result was that “in the years to come it would always find it difficult to match its principled policy-statements to its more qualified practices.”

Next on Revisiting India – Sinkandar Hayat Khan and the Unionists of Punjab: The Last Gasp of Hindu-Muslim Unity

Sources: Baker, Christopher. “The congress at the 1937 elections in Madras.” Modern Asian Studies 10.4 (1976): 557-589; Dove, Marguerite Rose. Forfeited Future: The Conflict Over Congress Ministries in British India, 1933-1937. South Asia Books, 1987; Muldoon, Andrew. “Politics, Intelligence and Elections in Late Colonial India: Congress and the Raj in 1937.” Journal of the Canadian Historical Association/Revue de la Société historique du Canada 20.2 (2009): 160-188; The Times of India, December 1936 – March 1937; Tomlinson, Brian Roger. The Indian National Congress and the Raj, 1929–1942: the penultimate phase. Springer, 1976; Witherington, C. A. “The New Constitution of India a Brief Survey.” The Australian Quarterly 9.4 (1937): 32-45

Pingback: 7. Sinkandar Hayat Khan and the Unionists of Punjab: The Last Gasp of Hindu-Muslim Unity | Revisiting India

It was really good article very lucidly explained, this article gave me clearcut idea about the 1937 elections.