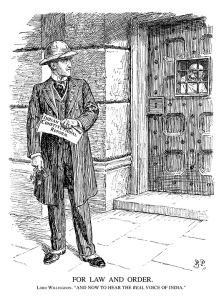

Punjab under martial law during the Non-Cooperation Movement

On 5 October 1920, Mian Fazl-i-Husain, a rising star of Punjab politics and member of both Muslim League and Congress, called an urgent meeting of his political colleagues to his Lahore house. His objective was to convince them to reject Gandhi’s Non-Cooperation Movement and the League’s Khilafat Movement, both of which were reaching fever-pitch at the time. Such unconstitutional agitation would only lead to lawlessness, he argued. Common masses were incapable of sticking to the idea of non-violence; eventually, blood will be spilled. But even before the meeting started, he knew that he was in a minority. Gandhi’s appeal of populist politics was simply too irresistible for Punjabi politicians to ignore. Defeated, Fazl-i-Husain tendered his resignation from both Congress and the League. In Rohtak, a similar story was playing out at the time. Chaudhary Chhotu Ram, a Jat peasant leader, thought Non-Cooperation Movement was dangerous and futile. Gandhi’s call for not paying taxes would only lead to confiscation of land from poor farmers, driving them further into the hole of poverty. Chhotu Ram’s arguments were shouted down, leading him to leave Congress as well.

As it turned out, loss of these two men was more than Congress could afford. Together, they went on to form the formidable Unionist Party, which dominated Punjab politics for the next two decades. Neither Congress nor Muslim League were be able to gain a foothold in the province when faced against the power of the Unionists. By late 1930s, the Unionists emerged as the most powerful political party in India which was truly built on a united Hindu-Muslim constituency. Yet, in the end, the Unionists, unable to adapt to the increasingly polarized political landscape of India, went the way of the dinosaurs. Forces of communalism, which had engulfed the nation by mid-1940s, swallowed the party whole, until it became a footnote in history. Continue reading

On Tuesday, 29 October 1929, the New York Stock Exchange opened under a cloud of fear. The market had been plummeting for the last five days and the brokers sensed that the worst was yet to come. They were not wrong. As the story goes, the opening bell of the exchange was never heard because the shouts of “Sell! Sell! Sell!” drowned it out. Within first thirty minutes, US$ 2 million evaporated into thin air and the slide continued. Phone lines were clogged and telegram service exhausted. By the end of the day, the market had lost US$ 14 billion – about 180 billion in today’s dollars. The ticker tape that recorded transactions ran for 15,000 miles! This was “Black Tuesday”, the beginning of the Great Depression, the longest, the deepest and the most widespread economic depression of the 20th Century. It would take the world twelve years to recover from it.

On Tuesday, 29 October 1929, the New York Stock Exchange opened under a cloud of fear. The market had been plummeting for the last five days and the brokers sensed that the worst was yet to come. They were not wrong. As the story goes, the opening bell of the exchange was never heard because the shouts of “Sell! Sell! Sell!” drowned it out. Within first thirty minutes, US$ 2 million evaporated into thin air and the slide continued. Phone lines were clogged and telegram service exhausted. By the end of the day, the market had lost US$ 14 billion – about 180 billion in today’s dollars. The ticker tape that recorded transactions ran for 15,000 miles! This was “Black Tuesday”, the beginning of the Great Depression, the longest, the deepest and the most widespread economic depression of the 20th Century. It would take the world twelve years to recover from it.