On the morning of 13 December 2001, Shekhar, the driver for the Vice President of India, was at the Parliament parking lot waiting for his boss. The Rajya Sabha, which his boss chaired, had been adjourned forty minutes ago, but the Vice President was still inside the building. At around 10:00 am, Shekhar heard someone shouting and suddenly a white Ambassador rammed into his car. By the time he got out of his car to have a word with the Ambassador’s driver, five men armed with AK-47s had poured out of it and begun shooting indiscriminately. Shekhar ducked for cover as other members of the Vice-Presidential security detail begun shooting back. A fire fight had broken out a few feet away from the heart of the Indian Government. In thirty minutes, it was over. All five attackers, who will be later linked to Pakistan, were dead. So were six of the policemen and security guards and a gardener who tended the Parliamentary gardens. The Parliament Attack was one of the deadliest terrorist strikes India had suffered through since its independence. In response the Indian Government started off the first nuclear crisis of the twenty-first century. A ten-month stand-off, where they stood precariously on the brink of an all-out war, was the closest India and Pakistan had come to nuclear annihilation. This is the story of that crisis.

The Parliament Attack had touched off one of the most difficult puzzles that the Indian leadership had been struggling with for more than a decade – how to handle a nuclear-armed Pakistan. Since Pakistan’s acquisition of nuclear weapons in late 1980s, it had grown more and more aggressive in pushing terrorism and the Kashmir Insurgency. As Pakistan’s leadership had calculated, the bomb gave them a cover against India’s superior military forces. They could bleed India by supporting the insurgency and be assured that India would not retaliate, for a retaliation could mean escalation to an all-out war and a nuclear annihilation for both countries. It was a game of perverse logic much like living next to a crazy neighbour (or a very smart neighbour pretending to be crazy) who keeps stealing from your house. Should you ever retaliate, he threatens to burn down both your houses.

All through the 1990s, while Pakistan continued to train and send increasing numbers of insurgents into India, New Delhi remained stuck in a strategic paralysis. While retaliations like air bombings or commando raids were considered, the risks were too great for India to ever go through with them. With the nuclear threat, coupled with the weak leadership that India suffered through during the decade of fractured politics, Pakistan seemed to have hit upon the perfect solution for its own security. The continued insurgency meant that the Indian Army remained occupied in Kashmir and thus not free to threaten Pakistan. It also meant that the Indian Government had to bear the crushing cost of securing India-Pakistan border against infiltration and the counter-insurgency campaign as opposed to Pakistan’s extremely cheap expense of running a few terrorist training camps.

As the decade progressed, Islamabad grew bolder. After the 1998 nuclear tests by both countries, situation deteriorated even further. In 1999, Pakistani soldiers dressed as insurgents infiltrated into the Indian territory leading to the Kargil Conflict. Again, under international pressure and fear of the nuclear bomb, Indian troops did not cross the border, but kept the fighting localized. Despite, the failure in Kargil, the conflict once again reaffirmed to the Pakistani leadership that the nuclear weapon could keep Indian retaliation in check as long as Pakistan could maintain plausible deniability. In the following two years, Pakistan kept pushing the activities further. In December 1999 the Indian Airlines Flight 814 was hijacked. In October 2001, Jaish-e-Mohammed carried out a suicide attack against the Jammu & Kashmir Assembly.

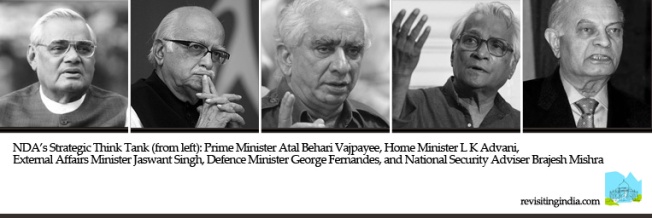

The Parliament Attack in December 2001 proved to be the last straw. The Kargil Conflict had underlined the Indian dilemma. Some of Indian top strategic thinkers had been asked to review the conflict in the Kargil Review Committee. Their conclusions clearly identified the problem: “it would not be unreasonable for Pakistan to have concluded by 1990 that it had achieved nuclear deterrence… [o]therwise, it is inconceivable that it could sustain the proxy war against India, inflicting thousands of casualties, without being unduly concerned about India’s ‘conventional superiority’.” The BJP Government was eager to try out a new strategy.

Four days after the Parliament attack, the cabinet met with military chiefs to discuss its options. The army chief, General S Padmanabhan, suggested a full-scale mobilization involving India’s three strike corps. Next day, Prime Minister Vajpayee gave the go-ahead. Operation Parakram was initiated involving close to 500,000 troops mobilized at the Pakistani border in preparation for an all-out war, the biggest troop mobilization in India since the 1971 War. Parallel to it, India put forward its demands for Pakistan to shut down all its support to the Kashmir Insurgency and handover 20 terrorists that India believed were living in Pakistan. In response, Pakistan mobilized its own troops. Armies of two countries stood against each other, on the brink of a major war. In fact, now the two neighbours came closer to a full-scale war than they had come to during the Kargil Conflict, when New Delhi had decided not to cross border into Pakistan.

The Indian Government was ready to give Pakistan taste of its own medicine. The rationale went that in the event of an Indian military attack, Pakistan would be restrained from using its nuclear weapons for the same fear of nuclear annihilation that India had. As the Defence Minister George Fernandes put it, “Pakistan can’t think of using nuclear weapons… We could take a strike, survive and then hit back. Pakistan would be finished.” It was an awfully large gamble, one that India had shied away from for the last ten years. But it was the only alternative to the paralysis India had been going through.

These developments had sent shockwaves through Washington. While Indian and Pakistani troops were facing each other, American troops were engaged in a battle with Al Qaeda and Taliban in the Afghanistan War, which had begun only two months ago. Not only would an all-out India-Pakistan War have proved disastrous for regional stability, the US also needed Pakistani troops on Pakistan-Afghanistan border watching out for Taliban and Al Qaeda leadership fleeing into Pakistan, rather than standing off against India. In fact, it was in those critical weeks that Osama bin Laden and Taliban leader Mullah Omar slipped into Pakistan. The US Government went on a diplomacy overdrive, trying to keep both sides from starting a war. The Americans also started pressurizing Pakistan to concede to the Indian demands.

On 11 January 2002, the Indian army chief declared that Indian mobilization was complete and the army was ready for war. On 12 January, largely under American pressure the Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf made a speech denouncing terrorism. He announced ban on six terrorist organizations including Jaish-e-Mohammed and Lashkar-e-Toiba and promised to arrest terrorists in his country. Nevertheless, he refused to hand over the twenty terrorists that India had demanded. The US was jubilant that a solution had been reached, although New Delhi remained sceptical. The Indian Government decided to hold off on the attack, but refused to remove troops from the border.

What emerged was a very precarious balance. US needed Pakistan to run its war in Afghanistan. India was torn between going to a possibly ruinous war or swallowing a humiliating defeat. Pakistan was facing mounting pressure from Indian army across the border and the Americans, its allies. Musharraf was also besieged at home. Supporting Americans after 9/11 had been a tremendously unpopular move in Pakistan. A defeat from India could prove to be politically disastrous for him.

And so Musharraf reneged on his promise. The arrested terrorists were soon let go and Lashkar-e-Toiba and other terror groups were allowed to operate as before. India watched these events with mounting anger. The crisis came to another boil quickly.

The Standoff required massive military movement. Pakistani journalist Ahmed Rashid reported of twenty-five miles-long army convoys.

On 14 May 2002, three terrorists dressed in Indian Army uniforms infiltrated an army camp near Jammu and killed 34 soldiers. India exploded with outrage. Preparations for war were resumed. On 22 May, Vajpayee speaking at a military base in Kashmir said, “The time has come for a decisive battle… and we will have a sure victory in this battle.” Faced with the threat of an all-out war, Pakistan brought back its nuclear card. On the same day as Vajpayee’s speech, a former chief of ISI made a statement: “if it ever came to the annihilation of Pakistan then what is this damned nuclear option for…. as they say if I am going down the ditch, I will also take my enemy with me.” Immediately afterwards, Pakistan began testing its nuclear missiles as threat.

However, the preceding months had allowed Pakistan to strengthen its defences at the border. To counter this, Indian Army decided to concentrate all three of its strike corps on a single point at the Rajasthan border. This meant more time was needed before the beginning of the war. It was the precious breathing space that the US needed to defuse the situation.

In addition to putting pressure on Pakistan to concede to Indian demands, on 31 May, the US began evacuation of non-essential personnel from its embassies and warned its citizens not to travel to the region. Other western countries immediately followed suit. Non-essential personnel from the American Pakistan Embassy had already been removed because of the Afghanistan War, so the order was effectively targeted towards India. The order came as a rude shock. As American businessmen begin to leave India, the order was interpreted in New Delhi as an American threat to punish Indian economically. This move softened Indian position considerably.

Parallel to it, one of top American diplomats Richard Armitage flew to Pakistan on 6 June to meet with Musharraf. In a two-hour meeting, he managed to get a vague promise from the Pakistani President to cease all terrorist activities. Armitage then flew to New Delhi and presented this promise as a hard pledge from Musharraf. The Indian leadership, eager not to leave any stone unturned before going to war, decided to hold back its troops for the moment.

In the succeeding months, according to the Indian Government, there was a drop in the rate of insurgent infiltration from Pakistan. Indian Government used this as an evidence for Pakistani goodwill, and decided to pull back its troops. In October 2002, the ten-month crisis was finally over, bringing a close one of the most dangerous periods in the last two decades.

There are several conflicting explanations given for why India finally pulled back. Some observers have argued that the threat actually worked, for India did not see high level of terrorism again until 2008. Others argue that India having failed to scare Pakistan, gave up rather than go to a possibly nuclear war. In late 2002, BJP Government was politically weak, due to several internal factors. Operation Parakram was costing the government Rs. 3 crore a day, which it had to finance by raising taxes by 4%. Combined with the American threat of economic punishment, the standoff had grown unpopular among the business community. There are still major gaps in our knowledge of what transpired in those heady days of June and why India turned away from a war it was committed to start. The new details will only emerge years from now, when the documents from this period are declassified.

Sources: Basrur, Rajesh M. “Kargil, terrorism, and India’s strategic shift.” India Review 1, no. 4 (2002): 39-56; Ganguly, Sumit. “Nuclear Stability in South Asia.” International Security 33, no. 2 (2008): 45-70; Mukherji, Nirmalangshu. December Thirteenth: Terror Over Democracy. Bibliophile South Asia, 2005; Raghavan, Srinath. “A Coercive Triangle: India, Pakistan, the United States, and the Crisis of 2001–2002.” Defence Studies 9, no. 2 (2009): 242-260; Schaffer, Howard B. The limits of influence: America’s role in Kashmir. Brookings Institution Press, 2009; Swami, Praveen. “Beating the Retreat.” Frontline 19, no. 22 (2002): 26.

A fascinating discussion is definitely worth comment.

I do believe that you should publish more on this issue, it may not be a taboo

matter but generally people don’t talk about such topics.

To the next! Kind regards!!